Eli Siegel (1902-1978), great American poet, critic, and founder of the philosophy Aesthetic Realism, is the author of Self and World: An Explanation of Aesthetic Realism; Hot Afternoons Have Been in Montana: Poems; Hail, American Development (Poems); Modern Quarterly Beginnings of Aesthetic Realism, 1922-1923; and James and the Children: A Consideration of Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw.

In 1925 his groundbreaking poem “Hot Afternoons Have Been in Montana” won the highly esteemed Nation Poetry Prize and swept America. In 1958 his book of poems with that title was nominated for the National Book Award and he was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize in poetry. For his centenary in 2002, the city where he grew up, Baltimore, Maryland, celebrated Eli Siegel Day, with proclamations by the mayor and governor and a celebration in Druid Hill Park.

Teaching in New York City for four decades, Eli Siegel gave thousands of thrilling lectures and classes on the arts and sciences, including many on the relation of science and art. Based on the principles he taught, the Aesthetic Realism Foundation provides a variety of classes, currently via video conferencing.

The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known

Many of Eli Siegel’s groundbreaking works are published in The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known (TRO), the international periodical he began in 1973. It explains what is happening in the world, and in people—in you. The Right Of contains immensely valuable and timely essays, poems, and lectures by Mr. Siegel and articles by Aesthetic Realism teachers and students. In every issue there is an editorial commentary by Ellen Reiss, who Mr. Siegel appointed the Aesthetic Realism Chair of Education. With scholarship and humanity, she has continued his work, together with many others.

Receive email alerts for each new issue of The Right Of, and announcements of events at the Aesthetic Realism Foundation.

Current issues of The Right Of:

We Are Still Self and World

(Issue #2160, May, 2025) The new issue of TRO honors the human self through understanding that’s accurate, kind, critical—and found nowhere but in Aesthetic Realism. There’s comprehension of the very best in us, and also of what weakens us most. This TRO answers, really answers, one of our most important questions: What is individuality? And it has some of the most beautiful and vital writing on that subject you will ever meet. read

Everyone’s Deepest Desire

(Issue #2159, April 9, 2025) What are people—what are we—most longing to understand about ourselves? Is there something we’re fundamentally going after, just by being alive—and do we need to be true to that something? Do we have purposes we should know about: one that will have us like ourselves; and one that will inevitably make us unhappy and have us dislike ourselves? This new issue has the authentic answers, presented thrillingly, including through an instance of art—the art of singing—and through a moving example about love. You’ll be reading a comprehension of self that’s the real thing and without parallel. read

Knowledge for This Time—& All Time

(Issue #2158, March 26, 2025). How does Aesthetic Realism differ fundamentally from other ways of seeing mind? What does it understand about the human self that people everywhere want and need to know? Is there such a thing as our largest desire, the thing we most need to go after in order to like ourselves? Does art (including the art of film) illustrate the structure of reality? And—what is the chief hindrance from within ourselves to our happiness? For answers to these questions—for the comprehension of yourself you’ve been longing for—read this issue, which begins publication of Eli Siegel’s urgently needed, ever so valuable lecture What Are We Going After? read

Imagination—about Hopes, Mistakes, & More

(Issue #2157, March 12, 2025). The new TRO is a mighty combination of depth and humor—something we’re yearning for! The examples of writing discussed in this issue—and the comment on them—are a great experience in what imagination is, and what it can do! So we proudly invite you to have the pleasure of reading “Imagination—about Hopes, Mistakes, & More.” read

Selected issues from the TRO Archives:

What Opposes Love?

(Issue #150) “The history of the world and the history of literature tell us that love has been opposed by hate and contempt….The play in French literature that stands for the discomfort of love, the unsettlement of passion, is the Phèdre of Racine…” read more

The Greatest Gift: Authentic Criticism

(Issue #820) “We publish here the great essay ‘Art as Criticism,’ by Eli Siegel….Aesthetic Realism shows…that no amount of praise or ‘acceptance’ will ever have us like ourselves. We want authentic criticism, criticism with enough knowledge in it.” read more

What Is Art For?

(Issue #226) “Aesthetic Realism sees the purpose of art as, from the beginning, the liking of the world more…. [Helen] Gardner’s mighty work, Art Through the Ages… tells carefully of Etruscan art, medieval Russian art, and certainly the art of Renaissance Italy; tells of the art of the American Indian and of United States art.” read more

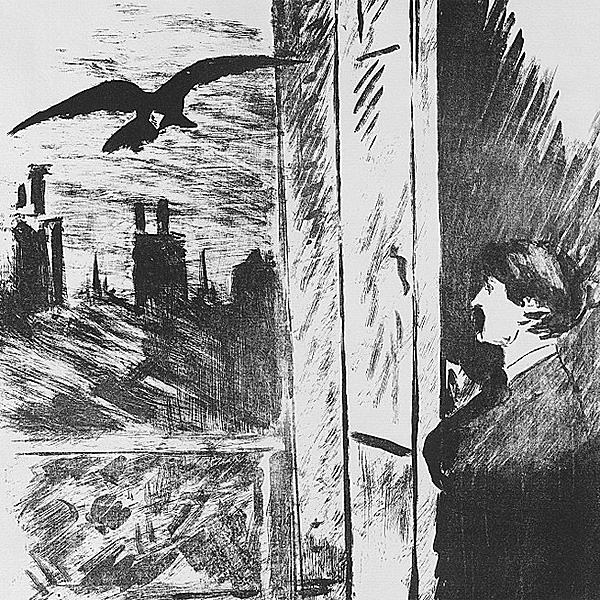

The Suppression of Good Will

(Issue #160) “One of these days, it will be seen that the chief thing man has suppressed so far is his good will. This, perhaps, is the largest matter in human history….The reason Edgar Allan Poe is so valuable as artist is his dealing so much with the consequences of suppressed good will.” read more

As We Were Saying

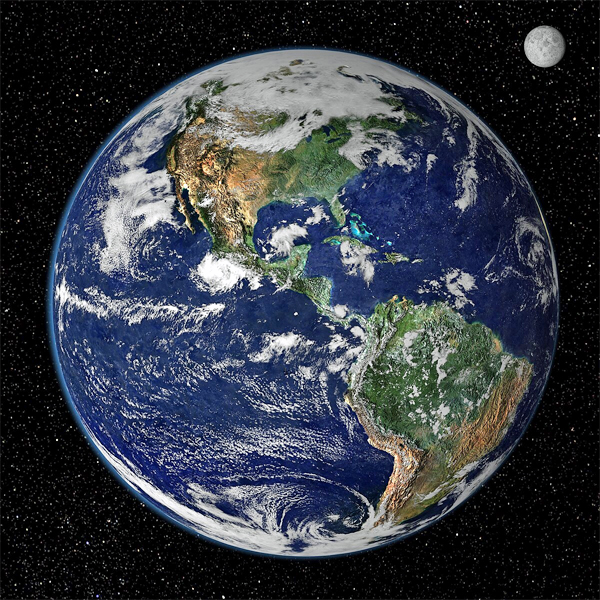

(Issue #85) “We have with us the structure of the world as it has been for a long time; and there is the structure of man. What is true about these? Aesthetic Realism has said that the oneness of opposites is the decisive explanatory thing…. Look at the fact that scientists, busy with space and time, have not been able to say whether the world or universe is infinite or finite; that is, unlimited or limited.” read more

The Shakespearean Awareness

(Issue #156) “Every dramatist has to be aware of the three great emotions which, when used not in behalf of a more just world but in behalf of a superior self, can do such harm….Shakespeare says much of fear, anger, contempt. Some of the highest points in the world’s literature have Shakespeare’s awareness of these three emotions.” read more

What Caused the Wars

(Issue #165) “It is necessary to see that while the contempt which is in every one of us may make ordinary life more painful than it should be, this contempt is also the main cause of wars. It was contempt that made for the trenches of France in 1915; it was contempt which made for the labor camps of the Second World War. It was contempt which made for that awful mode of retaliation called Nazism.” read more

The Two Pleasures

(Issue #162) “One thing that is clear in the history of man is that he has had pleasure of two kinds. Man has had pleasure from seeing a sunset; from Handel’s Messiah; from seeing courage in someone; from a great rhythm in words. He has also had pleasure from making everything he can meaningless….Man, then, praises; he also diminishes.” read more

Aesthetic Realism Is Education

(Issue #12) “Aesthetic Realism believes that a person who doesn’t like the world on an honest basis is not educated. The purpose of all education is, as Aesthetic Realism sees it, to find sense in the world; also honestly to hope to find sense in the world when that finding, as it often is, is difficult.” read more

Knowing Oneself

(Issue #200) “Geoffrey Chaucer, the first unquestionably eminent English poet, said about six hundred years ago in his ‘The Monk’s Tale,’ this: ‘Ful wys is he that kan hymselven knowe!’ Well, even now, Chaucer is not agreed with, though certainly people often act as if they felt it was wise to know oneself.” read more

America Has Literature

(Issue #284) “The first American novel that impressed Europe was The Spy of 1821 by James Fenimore Cooper….It is important to relate a writer like Cooper to the young people in Henry James’s Turn of the Screw. Miles and Flora represent wickedness in a field of engaging innocence. Innocence and wickedness meet more deeply in the novels of Cooper than is recognized.” read more

The Fight

(Issue #151) “The greatest fight man is concerned with, is the fight between respect for reality and contempt for reality that has taken place in all minds of the past and is taking place now. There are three places in literature which make the fight between respect and contempt clearer….Sonnet 66 of Shakespeare; Baudelaire’s ‘O Mort, vieux capitaine’; and Shelley’s ‘Ode to the West Wind.’ read more

Our Dear Minds

(Issue #239) “Perhaps the person who was most successful in philosophic history was John Locke, 1632-1704…. Locke meant a good deal to the plain, money-getting person; and still means a good deal….Today, I deal chiefly with John Locke; but I hope to show that all the philosophers…present a world we can see as usable for our lives, deeply on our side.” read more